|

|

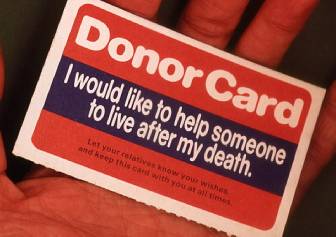

Organ donation is encouraged by most rabbinical authorities.

| |

Judaism’s perspectives on Organ Donation After Death

-- Gabrielle Loeb

Although many Jews believe that Jewish law forbids organ donation, most

rabbinical authorities not only permit it, but also encourage it. In 1990, the

Rabbinical Assembly of America approved a resolution to “encourage all Jews to

become enrolled as organ and tissue donors by signing and carrying cards or

driver’s licenses attesting to their commitment of such organs and tissues upon

their deaths to those in need.” Organ donation during life is generally

permitted as long as there is little risk for the donor and great benefit for

the recipient, but in the case of an already deceased donor, the risk is not an

issue. For already deceased donors, the main issues are Kavod Ha-met

(honor of the dead) Nivul Ha-met (disgrace if the dead), and the

definition of death.

Kavod Ha-met is the reason for the extensive Jewish laws regarding burial

customs. The body must be treated with respect since it is God’s property; we

are simply borrowing our bodies for the duration of our lives and we must return

them at death unblemished. This is the reason that permanent tattoos and

piercings are forbidden. Because of Kavod Ha-met, delaying the burial of

the deceased or gaining benefit from a dead body are considered Nivul Ha-met,

disgrace to the dead, and are therefore forbidden. This obviously poses a

problem since organ donation can delay the burial and allows us to benefit from

the dead body.

This problem with delayed burial and benefits from the dead body, however, is

superceded by the commandment Pikuach Nefesh, saving a life, which takes

precedence over every other commandment excluding murder, idolatry, incest, and

adultery. The Talmud Tractate

Yoma 85b says,

referring to the commandments, “You shall live by them, but you shall not die

because of them.” This means that we should not “stand idly by the blood of

[our] neighbor” (Lev.

19:16) because of the less important commandment of Kavod Ha-Met.

In fact, not only does this commandment cancel the Nivul Ha-met, it gives

Kavod Ha-met because it enhances the respect for the deceased since it

allows the donor to fulfill the mitzvah of Pikuach Nefesh. Donating

organs is therefore an honor to the deceased. In addition, the transplanted

tissue will ultimately be buried with the recipient, so the burial would not be

an issue even if it were overridden by Pikuach Nefesh. Finally,

Pikuach Nefesh is even more important to donors since they are thereby

saving the lives of both the recipient and any potential living donor whose life

might be at a slight risk due to the surgery involved in donating organs.

Because of the organ shortage, the Conservative movement’s Committee on Jewish

Law and Standards ruled in 1995 that organ donation is an obligation because not

doing so would be murder to the potential recipient and endangers the lives of

living donors.

Besides Pikuach Nefesh, Hesed is another reason supporting organ

donation. Hesed, acts of kindness, are not mandatory, but we are commanded to

“walk in God’s ways” and this would include helping those in need. Such progress

has been made in transplants in the past fifty years that they are now

acceptable therapeutic options instead of experimental procedures, and therefore

Hesed, in addition to Pikuach Nefesh, is more ensured. In 1954, the

first kidney was successfully transplanted followed by a liver in 1967, a heart

in 1968, a lung in 1983, and a pancreas in 1996. New genetic engineering

techniques will soon enhance the immune system’s ability to accept alien organs

and immunosuppressant drugs. In 1998, 21,000 transplants took place including

kidneys, livers, hearts, pancreases, and bone marrow. Success is now measured in

terms of years and quality of life following transplant instead of survival of

the surgery. When organ transplantation was still very experimental and

endangered life, Jewish law restricted it much more; however, with all this

recent progress in organ transplantation and with the organ shortage, donated

organs are sure to be an act of Hesed as well as Pikuach Nefesh.

In addition to following God through acts of

Hesed, we must practice Kiddush Ha-Shem, sanctifying God’s name, by

acting in a way to honor God and the Jewish people. With the current organ

shortage (In 1998, according to Lamm’s book

The Jewish Way in Death and Mourning, 4,855 people died waiting for

donors, most of whom were cadaveric donors. Every sixteen minutes on average,

one more person joins the 63,000 on the waiting list of the United Network for

Organ Sharing), Jewish organ donations would make the Jews look more honorable,

and it would therefore sanctify God’s name. On the other hand, if Jews were to

refuse to donate organs, this would look bad for God and the Jewish people, and

a forbidden Hillul Ha-Shem, desecrating God’s name. In fact, this is

exactly what is happening now, and that is one of the many reasons that

rabbinical authorities permit and even encourage organ donations: As Dorff

explains in his book

Matters of Life and Death, while 60% of the general population are willing

to donate organs, only 5% of Orthodox Jews are, and the statistics are similar

for other Jewish denominations. As a result of Israel accepting far more organs

than they provide, Israel has been banned from Europe’s transplant network

Eurotransplant. Israel’s exclusion from Eurotransplant not only is a huge Hillul

Ha-Shem, but it also increases the shortage in Israel of organs for people on

the long waiting list for transplants.

Even with the commandments of Pikuach Nefesh, Kiddush Ha-Shem, and

Hesed which take place in organ donation, it is not given a complete

authorization. There should be an advance directive saying that the deceased

wishes to donate his or her organs. If no advance directive is made, however, it

can be assumed that the deceased would be honored to be given the opportunity to

perform Pikuach Nefesh. In addition, the most restrictive Orthodox rabbis

require that there be a specific patient Lefaneinu, “before us,” who

would otherwise die or lose an entire physical faculty. This means that if the

potential recipient can see with one eye, they would not permit a corneal

transplant. These rabbis would also reject donations to organ banks because

there would be no particular known patient who would be served immediately by

the donation. Most Jewish authorities agree, however, that a donation is

justified to improve impaired vision, and that a donation to an organ bank is

justified as long as there is enough demand for that particular organ that it

can be safely assumed the donated organ will eventually be used.

The final restriction placed on organ donation concerns how death is defined. In

some cases the line between life and death is hazy, so it needs a precise

definition. Some rabbis go by the respiration test of placing a feather under

the nostrils and seeing if it moves; they consider death to be defined as

respiratory arrest. Others claim that respiratory arrest is only considered

death because it is a reliable sign of cardiac arrest, which is the true

definition of death. Since an organ donor must be dead according to Jewish law,

the moment when organs can be collected is debated. In addition, Jewish law

states that we must wait before we assume that a person is dead since they may

simply be unconscious or in some other state resembling death. However, waiting

would obstruct organ donation since the heart must be collected immediately, and

the heart must be beating to keep the other tissues alive. This problem was

solved by sphygmomanometers and electrocardiograms, which can measure breath and

heartbeat and remove the need for waiting. The issue of donating a heart is

further complicated, however, if a person whose heart is beating is considered

alive, yet the heart must be beating to collect organs. So how can it be that

the Chief Rabbinate of Israel approved heart transplants in 1998?

The answer is progress in medicine and more advanced ways of diagnosing death

being developed. Instead of using a feather or trying The answer is progress in

medicine and more advanced ways of diagnosing death being developed. Instead of

using a feather or trying to hear a heartbeat, a flat electroencephalogram is

used to declare someone officially dead. If someone has a flat

electroencephalogram, that person is and forever will by unable to breathe or

pump his or her heart himself or herself. Almost all Jewish authorities agree

that a flat encephalogram can be used to determine death. It indicates the

cessation of spontaneous brain activity and qualifies the patient as being

brainstem-dead instead of heart-dead or breathing-dead. Brainstem-dead should

not be confused with brain-dead, however, which is the cessation of higher

cerebral functions like intellect and memory that are lost in Alzheimer’s or a

vegetative state – in such cases the patient is considered alive and organ

donations are therefore not permitted. Going by the heart-death definition would

make less sense because a decapitated animal’s heart still beats for a short

while, and because the heart can beat even without a body as long as it is

nourished. Both The Conservative and Reform movements accepted

electroencephalograms (since they indicate the cessation of brain activity) as

the moment of death, and the Orthodox chief rabbinate followed suit twenty years

later, as did the Rabbinical Council of America in 1991. Since brainstem death

was approved and is the major rabbinic opinion (although some rabbis reject this

halachic decision), heart transplants and organ transplants can take

place.

However, there are other impediments to organ donations besides rabbinical

concerns: donors often have misconceptions about the process and cost of

donating organs, and sometimes other psychological factors come into play.

Donors sometimes wrongly believe that the donor’s body will be mutilated and the

funeral will be delayed a long time. On the contrary, the body is sewn up

quickly, and the funeral can occur without much delay. In addition, closed

caskets would prevent any surgery from being noticed. Secondly, some donors

assume that they must pay to donate organs. The truth is that the recipient (or

their insurance) pays for the organ transplant, not the donor. Other donors

believe that if their doctors know that they have agreed to donate organs, the

doctors would not try as vigilantly to keep them alive. This too is a myth since

the physician team for the organ transplant is entirely separate from the

physician team that would normally care for the patient, to serve this exact

purpose. Still other potential donors are hesitant due to an aversion to even

contemplate death, let alone things that would happen afterwards. People also

tend to imagine donating organs as though they would be conscious when the

donation would take place, and they imagine what the surgery would feel like for

them although they would have to be brainstem-dead and therefore could not feel

it.he body for three days after the death, during which the soul hovers over the

grave. Even for the first twelve months, while the body disintegrates, the soul

has a fleeting connection with the body, during which it comes and goes to and

from the body. Finally, there are spirits who live on after death in bodily

form. If the soul comes to the body, one might be uneasy with the idea of the

body “not being complete.”

Incompleteness of the body is also an issue to people when they contemplate

resurrection; they believe that in order to be resurrected in one piece, they

must be buriedIncompleteness of the body is also an issue to people when they

contemplate resurrection; they believe that in order to be resurrected in one

piece, they must be buried in one piece. Two main arguments contradict this

thought. First, organs which are not donated simply disintegrate in the ground

(unless the body is preserved, which is forbidden). Secondly, if God could make

the world from nothing, it should be relatively easy for God to make something

from something that once existed but just decomposed. When resurrection comes,

Jews will be resurrected regardless of parts missing or even whole bodies

missing. Maimonides further explains that people should not even consider a

bodily resurrection since resurrection is of the soul, not the body, since the

world to come will have no bodily functions of eating, drinking, anointing, or

sexual intercourse. Regardless of ones beliefs about resurrection, however, the

overriding rule is again

Pikuach Nefesh: saving a life immediately is far more important than

beliefs about what lies ahead.

But what if donating organs is not saving any life at all? What about donating

one’s body to science? As long as the body parts are preserved to bury, the

deceased’s (and his or her family’s) wishes are respected, and the family can

return to their lives even without the psychological closure of an immediate

burial, most rabbinical authorities permit donating one’s body to science for

the same reason as they permit organ donation. It is considered

Kibud Ha-Met, not as Nivul Ha-met, since dissection, necessary to

train physicians, facilitates the performing of Pikuach Nefesh, which is a great

honor. Also, it is Hillul Ha-Shem for Jews not to do it and

Kiddush Ha-Shem for Jews to do it, unless there is already ample supply

of bodies to dissect, in which case Jewish donations are unnecessary and

therefore unjustified. Some orthodox rabbis, however, again reject donating a

body to science as a justifying reason, since there is no specific patient who

is to gain from the donation.

Another question that is brought up concerning organ donation is whether the

donor can be paid. Even the United States is hesitant to condone such a

practice, although Pennsylvania does allow payment of renewable tissues such as

blood, hair, and semen. While the United States does not favor such practice

because vulnerable populations could be abused and exploited (while not being

able to afford organs which they may need), Jewish law does not favor such

practice because the body belongs to God, and we cannot sell what is not ours.

The Halachic Organ Donor Society

in New York City, whose mission is to spread information about Jewish legal

matters and rabbinic beliefs about organ donation, helps Jews donate organs in

accordance with their specific halachik beliefs. They try to raise awareness

about the importance of organ donation and to combat the myth that organ

donation is contrary to Jewish law.

There are numerous reasons for Jews to become organ donors; most reasons against

that choice are simply misconceptions. Jews should consult their own rabbi to

discuss the issue of organ donation. Most rabbis agree, however, that it is our

responsibility as Jews to honor God’s name and to save lives by giving the gift

of life even after are lives have terminated through the act of organ donation.

As

Mishnah Sanhedrin 4:6 says, “Whoever saves one life, it is as if he

saved the entire world.”

Previous Features

Did you enjoy this article?

If so,

- share it with your friends

so they do not miss out on this article,

- subscribe

(free), so you do not miss out on the next issue,

-

donate

(not quite free but greatly appreciated) to enable us to continue

providing this free service. donate

(not quite free but greatly appreciated) to enable us to continue

providing this free service.

If not,

|