| About Free Subscription Donate Contact Us Links border="0" /> Archives | |||

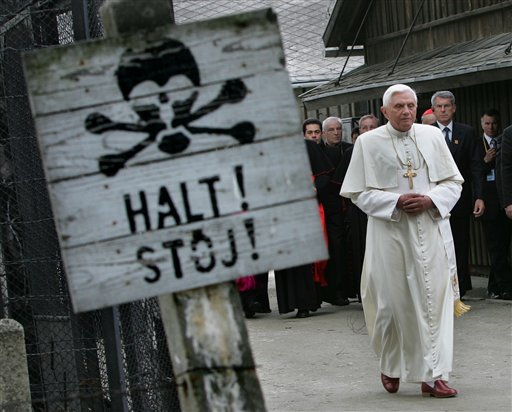

The Holocaust Was Not Christian Benedict's historic failure at

Auschwitz. Pope Benedict XVI had such a moment before him when he visited Auschwitz in May. In this time of resurgent Holocaust denial by the president of Iran and others, Benedict's visit, watched by the world, was historically and politically important. This German pope reaffirmed with his presence and words the falsity and mendacity of Holocaust denial. He came, he said, as "a duty before the truth and the just due of all who suffered here." Yet the good he did by visiting Auschwitz was overshadowed by the address he delivered there, which offered none of Brandt's genuine emotion or John Paul's humility, and which glaringly failed to heed Benedict's own self-proclaimed duty to truth. Instead, Benedict clouded historical understanding, evaded moral responsibility, and shirked political duty. Benedict falsely exonerated Germans from their responsibility for the Holocaust, by blaming only a "ring of criminals" who "used and abused" the duped and dragooned German people as an "instrument" of destruction. In truth, Germans by and large supported the persecution of the Jews, and many of the hundreds of thousands of perpetrators were ordinary Germans who acted willingly. It is fundamentally false to attribute culpability for the Holocaust wholly or even primarily to a "criminal ring." No German scholar, no mainstream German politician, would today dare put forth Benedict's mythologized account of the past. Benedict did say correctly that the "rulers of the Third Reich wanted to crush the entire Jewish people." But he then turned the Holocaust into an assault most fundamentally not on Jews but on Christianity itself, by falsely asserting that the ultimate reason the Nazis wanted to kill Jews was "to tear up the taproot of the Christian faith," meaning that their motivation to kill Jews was because Judaism was the parent religion of Christianity. As every historian and even the casual student knows -- and as the Church's historians ordinarily take pains to emphasize -- the German perpetrators saw the Jews as a malevolent and powerful "race," not a religious group. Their desire to annihilate Jews had nothing to do with anti-Christianity. Benedict's failure to say that the Germans slaughtered Jews because they hated Jews is part of his overall failure to confront the historical centrality of the Holocaust in the Germans' mass murdering. This omission governs his address in subtle and unsubtle ways, including his intention not to use either name for the crime, Holocaust or Shoah (Shoah was inserted at the last moment after the speech's text had already been distributed), and his devoting explicitly to the slaughter of the Jews less than 200 out of almost 2,300 words, with many of these few words contributing to his Christianizing of the Holocaust. It is of course laudable to acknowledge and remember that the Germans murdered other peoples, but in Auschwitz 1 million of its 1.1 million victims were Jews. And it was a death factory designed for Jews. From Benedict's address you would not know these basic facts or their importance. In this and other ways, Benedict severed and obscured all connection between the Catholic Church, Christianity, and the Holocaust, which is a huge step backward from the earlier positions that John Paul II and many European Catholic churches adopted. Stunningly, Benedict walked through the gates of Auschwitz, a graveyard of one million Jews, and did not once mention the prime mover of the Holocaust: anti-Semitism, let alone the millennial anti-Semitism of Christianity that was for centuries ubiquitous in Europe, and that culminated in Nazism and the Holocaust. Whatever differences existed between Nazi anti-Semitism and its Christian anti-Semitic seedbed, anti-Semitism is the unavoidable causal, historical, and moral link connecting the Church, the Nazis, and Auschwitz. Since Vatican II in 1965, the Church has forcefully condemned anti-Semitism, even declaring it a sin. Yet Benedict, a political and moral beacon to a watching world, stood in Auschwitz negligently silent during our time of anti-Semitism's renewed danger, not uttering a word against anti-Semitism and not reminding humanity of what this evil had wrought there: a death factory. At length Benedict wondered about where God was. A Churchman's question. But he conspicuously failed to ask where the Church was. Benedict's appeal to the mysteries of God's ways thus obscured even the most discussed aspects of the Church's and Pius XII's conduct during the Holocaust: Why they didn't speak out. Why they didn't do more to help Jews. Such evasion and prevarication are no way for a moral leader to confront moral responsibility, let alone to carry out the Church's moral imperative of repentance and duty of repair. In his brief papacy, Benedict has shown much goodwill in continuing to improve the Church's ever better stance towards and relations with Jews today. But with his whitewashing of the past -- exonerating both the German perpetrators and the Church, universalizing the Holocaust, and de-emphasizing its purely anti-Jewish thrust -- he stands before the world in stark and unfavorable contrast to John Paul II who on similar occasions spoke with forthrightness, humility, and in the spirit of the Church performing needed repair, and especially made pains to warn the world of the evils of anti-Semitism. Benedict has also turned the clock back on what the Catholic Church had, in the decade prior to his papacy, been acknowledging: that the Church must confront its role in propagating anti-Semitism and in persecuting Jews; that many Catholics, moved by the Church's anti-Semitism, participated in the Jews' persecution and slaughter; that the Church should have done much more to aid the assaulted people. And, most of all, that the Church must, in the words of the French Bishops 1997 declaration, confess its "sin" and utter "words of repentance." Only then, can Benedict rightly approach the victims to ask for reconciliation. |

|||

© 2006. Permission is hereby granted to redistribute this issue of The Philadelphia Jewish Voice or (unless specified otherwise) any of the articles therein in their full original form provided these same rights are conveyed to the reader and subscription information to The Philadelphia Jewish Voice is provided. Subscribers should be directed to http://www.pjvoice.com/Subscribe.htm. |